Welcome to Maid Spin, the personal website of iklone. I write about about otaku culture as well as history, philosophy and mythology.

My interests range from anime & programming to mediaevalism & navigation. Hopefully something on this site will interest you.

I'm a devotee of the late '90s / early '00s era of anime, as well as a steadfast lover of maids. My favourite anime is Mahoromatic. I also love the works of Tomino and old Gainax.

To contact me see my contact page.

The Island of Britain is criss-crossed with thousands of paths, some old and some new, some busy and some remote, some paved and some not. This complex network of connections has grown over the course of millennia pushed and pulled by forces both top-down and bottom-up to form an efficient system of transport, compliant to the changing technology of road transportation. The growth of such ancient routes are usually enigmatic, but follow a chaotic principle which can be traced back to the most humble origins. It would have been natural for the first humans in an area to follow pigtracks through woods: little paths taken by pigs or deer between feeding grounds often amounting to nothing more than a line of compressed grass. These paths would become wider and more trodden by humans also wishing to move between such areas. And from there the evolution from footpath to bridleway to gravel trackway to highway is clear, all because of the slight trace left by an ancient pig. This "butterfly effect" is both chaotic but ordered, because routes which aren't useful will natural fade in favour of those which are useful; creating an efficient network by the natural algorithm of survival-of-the-fittest. I want to document a little about how that system developed in my homeland of Britain.

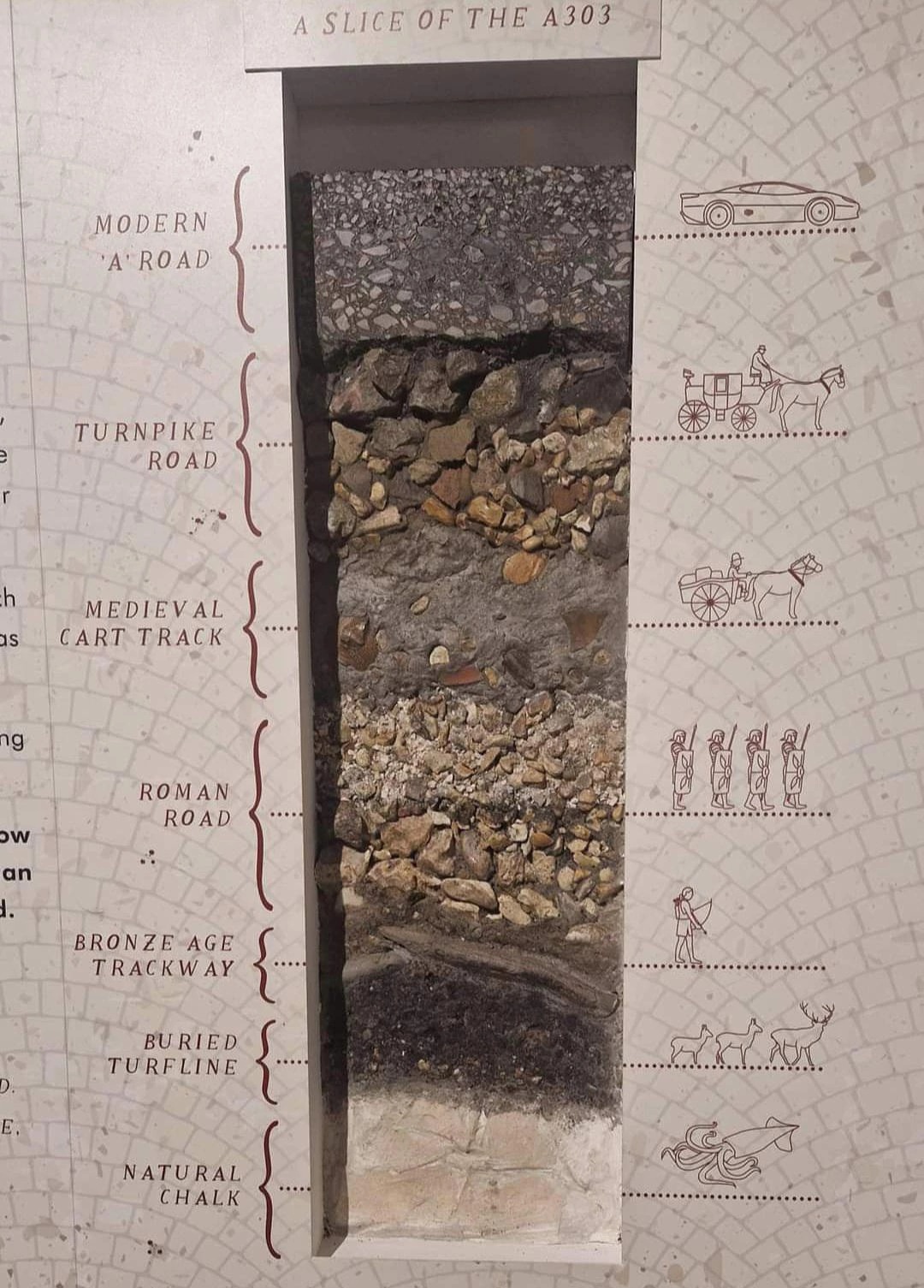

^A cutaway of a portion of the A303, Wiltshire.

^A cutaway of a portion of the A303, Wiltshire.

In the time before the Roman invasion, roads on the Island of Britain were generally made up of local links between villages, carved into the landscape by frequent use. Long-distance routes did exist, as communication between distant areas of Britain in this era is certified archaeologically, but these routes seem to have been more like itineraries listing which villages to pass through in which order rather than cohesive roads. Many of these pathways have been around for many thousands of years, and represent by far the eldest infrastructure still in use today.

A common form of extant ancient roads are "holloways", these are paths so old that the ground itself has sunk beneath them, creating deep gullys. These are most common in the South of England, where the chalk bedrock is easier to erode, bu they are also common in the West Country and Wales, where many of them are actually man-made. Due to the high winds and harsh weather of these upland and coastal regions, ridges of rubble and earth are built alongside roads and topped with dense hedgerows to act as windbreaks and to provide some shelter to travellers. These defences create their own holloways, which over time blend seamlessly with the landscape to create what is known as "Bocage" terrain. Meanwhile in the plains (and ancient forests) of middle England, roads remained far more abstract. Milestones were commonly used in conjunction with signposts to reassure travellers they remained on track, although the actual paths between these nodes would shift with time and the seasons. Most monoliths found in England are actually milestones originally placed at crossroads, letting people know they were at a specific node on their journey. As an aside, these cross-road stones eventually grow traditions for themselves, often being used as places of execution or as burial spots for criminals. Often crosses would be placed at crossroads, many of which were unfortunately destroyed during the reformation, but can still sometimes be seen (think Banbury Cross or Charing Cross). While these roads were self-perpetuating affairs, the earliest roads which could properly be described as projects of state infrastructure are the board-walk causeways of the English fenlands. These structures involved ridges of rubble being placed through marshland and topped with planks, allowing pedestrians and horses to traverse over boggy wetlands without getting wet. Because of the great preserving forces of the stagnant fenwater, many hundreds of these planks have been found, mapping out several routes between islands such as Ely or Glastonbury with the mainland. However these projects pale in comparison with what was coming next.

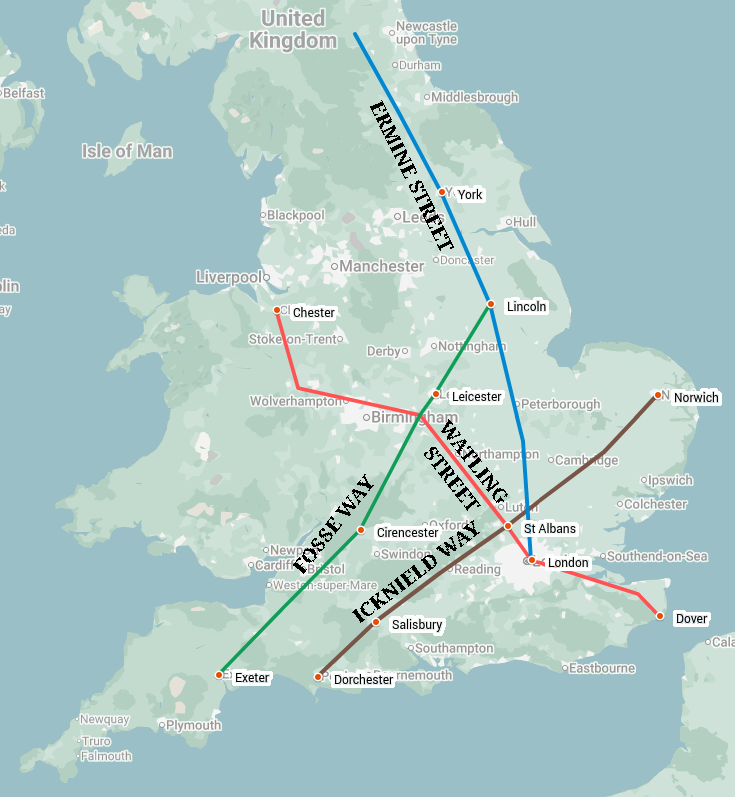

The Roman occupation of Britain brought with it the masculine engineering of the Roman Road. In the main unfazed by nature, Legions constructed the famous straight-line military roads across the English and Welsh landscape, ploughing through field and forest and river. This was a system of civil engineering not seen again until the United States' "road first, town later" mentality. Roman forts and cities were built where the roads intersected, rather than the roads being built between existing settlements. This unnatural system forced the structure of British civilisation to conform to it by strength of arms, and the effects of this project are evident in even modern population distribution. At the core of the Roman system were three roads: Watling Street from Dover to Chester via London; Ermine Street from London to York (and beyond) via Lincoln; and the Fosse Way from Lincoln to Exeter. These three roads made up an efficient system of connections allowing Roman Legions to get from their bases to anywhere in the country as efficiently as possible. However even these new Roman highways weren't built in a vacuum. The City of St Albans, for example, was a nexus for roads in Roman Britain, with Watling Street and Akeman Street (London-Cirencester) passing through. Also passing East-West through the city is the mysterious "Icknield Way", potentially the oldest known long-distance route in Britain. Icknield Way is attested for by Caesar as a primary artery of the Bretons, following a near-straight course from Norwich through Bury St Edmunds and St Albans to Old Salisbury and the Dorset Coast. This general route (the exact course of which probably shifted over the centuries) seems to be the most active axis across which Preroman Britain operated: along this line were found the most powerful tribes of the era, and are many of the most ancient sites in England such as Stonehenge. It matches up somewhat with "St Michael's Alignment", as I explored in my article from June too. These Roman Roads were truly fearsome feats, not many structures last 2000 years, and fewer still can remain useful in their original purpose for that long too. The routes of these roads are so integral to Britain that they number alongside rivers and mountains in our demarcations of land. Take my home county of Warwickshire, for example. Her borders are marked by natural features: the ridge of the Cotswold Hills, the course of the River Avon, and the entrenched straight-line of Watling Street.

^The county of Warwickshire (drawn by me). Watling Street can be seen in the Northeast. Additionally the Fosse Way can be seen running through the county SW-NE.

^The county of Warwickshire (drawn by me). Watling Street can be seen in the Northeast. Additionally the Fosse Way can be seen running through the county SW-NE.

The centuries after the departure of the Romans saw the emergent Anglosaxon states live in the shadow of their Roman ancestors. Many of the Roman roads fell into disuse, although the most important remained heavily used and well-kept by their new caretakers. In fact the Roman Roads were pivotal in the Anglosaxon invasions themselves, with the invading armies using them to move quickly into the heart of the island and take up fortified positions within the ruins of Roman "castra" (giving us all the cities suffixed with "chester" or variations of). By the time of the 11th century, it is noted by scholars that the King paid for the upkeep of just four paved "royal highways", the names of which are familiar: Watling, Ermine, Fosse and Icknield. Ermine Road in particular became of great importance as Angloscottish relations soured. The road had been used by King Harold Godwinson's army in 1066 to quick march from London to Stamford Bridge and back down to Hastings, at an average pace of approximately 35 miles per day (very fast). By the time of Edward Longshanks it had been renamed to "The Great North Road", and in fact continued North from the new castle in Newcastle all the way to the foot of Arthur's Seat in Edinburgh. This route, now known as the "A1" would become the most important link between the two nodes of the then disunited kingdoms. Famously after the death of Queen Elizabeth I in 1603, Sir Robert Carey made the fastest ever journey (at the time) from London to Edinburgh along the Great North Road in order to notify James VI that he was now VI & I, taking only 2 days to do so (approximately 42 hours, giving an average speed of 10mph). It is reported that the new King was unimpressed, calling Sir Carey's enthusiasm and speed unnatural and indecent, and he was never afforded a position in James' court. The list of royal roads would slowly expand, with the Great Essex Road (extending to Yarmouth), the Great Western Road (to Bath and Bristol), and the Portsmouth Road radiating out from London as those respective port cities grew in importance. The vast majority of roads were however unkept, only repaired by commission from a local noble or in common by the peasantry. Responsibility for the upkeep of said roads was held solely by the landowner, meaning the quality of roads was very unpredictable and passage was sometimes impossible.

^The four Royal Roads of Mediaeval England. Red

^The four Royal Roads of Mediaeval England. Red

In 1555 Parliament enacted the Highways Act, which set up "Turnpike Trusts": state bodies for the upkeep of roads. These trusts would levy funds by way of tollgates, positioned at chokepoints in the landscape such as bridges or fords. These tolls' values would depend on what you were moving, higher rates were taken from those transporting luxury goods, while walkers without animals would generally go free. At first these tolls were limited to degraded or difficult to maintain roads, but by the 18th century were widespread and covered every commonly taken route across the country, making travel increasingly expensive for the average merchant to move goods even short distances. During this period the Inclosure Acts also consolidated the power of landlords over their land, removing many of the ancient rights traditionally enjoyed by the lower classes. The combination of these factors caused civil unrest and discontent, with several cases of trespass ending up in the courts, which eventually upheld the inviolable right of passage along established paths for all. Westminster wasn't the only cause for the financial worries of travellers in this era however: the 18th century saw the apex of the "highwayman". England's most romantic criminals, the highwaymen took advantage of the increase in intercity travel to stage lucrative heists. As another measure of transport efficiency, famed highwayman Dick Turpin again broke the record up the A1 with his 14 hour race from London to York in order to provide himself with an alibi (a record-breaking 15mph).

By the turn of the 20th century the scope of land transportation had changed. Horse-drawn vehicles, while still the most common form of transport, were being replaced with new technologies such as bicycles or the motor car. The old cobbled or gravelled roads were no longer fit for purpose, so inventor Edgar Purnell Hooley created "tarmac", a hardy mixture of tar and sand which provided a much smoother surface for faster moving vehicles. Radcliffe Road in Nottingham (just over the Trent Bridge) became the first road to be "tarmacked", an innovation which quickly spread across the country, Europe and the wider world, beating out the lesser but potentially cooler named "Lava Stone" being developed in London. In 1920 the Roads Act reformed the old Turnpike system, removing the vast majority of tolls, and charging a duty on all road vehicles at purchase as well as requiring a license for use of the road network by carriage or motor car: today's "road tax". The modern classification of roads was also devised, initially at 3+3 levels:

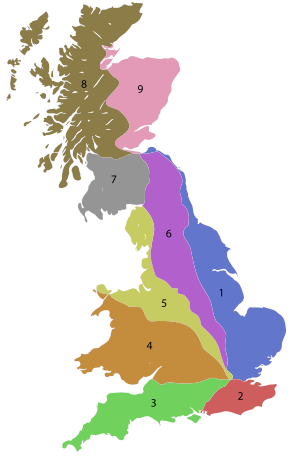

This system worked off of a radial system, emanating from London and Edinburgh. Zones 1-6 radiate from London across England and Wales, while zones 7-9 radiate from Edinburgh across Scotland. These are all bounded on their anticlockwise side by the corresponding 1-digit A road. So all roads within the area bounded by the A3 and A4 would be in Zone 3, for example. Many of these routes followed existing ancient pathways, upgraded to conform with modern needs.

^The Road Numbering Zones of Great Britain.

^The Road Numbering Zones of Great Britain.

This system worked well enough, until the motor car began to dominate a few decades later. In 1936 the government of Sir Chamberlain set out to build a new network of roads to cater for the modern motor vehicle, inspired by a visit to Hitler's new Autobahn system in Nazi Germany. The "Trunk Roads Act" brought all "major" A-Roads under direct government control for the first time since the Roman occupation, although the government was unable to get through many of the more imposing changes they wished for, and were thus unable to build many new roads at this time. This all changed after World War II however, when the government gained unprecedented powers to appropriate land for the good of the nation. These dictatorial rights were, as expected, not relinquished after the end of the war, and the government created a new classification of road to add to the list: the "M-Road" or "motorway", a route on which the public has the right to travel by motor vehicle only. This was the first time public roads had become inaccessible to pedestrians, a fact which many protested at the time, even if they made travel times so much faster. The first motorway was opened in 1958, a small part of the now M6 acting as the Preston Bypass in Lancashire. This was followed a year later by the far more substantial M1, a "replacement" to the Great Northern Road, stretching between London and Leeds. The motorway revolution would pick up in the 1960s, with expansive swathes of countryside bulldozed to construct these new tarmac rivers. Unlike previous road infrastructure projects, British motorways were generally built as totally new routes from the old system of ancient roads, although due to the fundamental geography of the nation many would still follow the general routes of old routes. Watling, Ermine and Fosse now became the M1, the M2/M40, and the M5; with the A3, A4, A6 and A8 being all-but replaced by their M counterparts. Even the ancient city walls of Roman London have been replaced with the M25... The fastest recorded journey from Lands End to John o'Groats was actually (purportedly) made in 2020 in just 9hr36, by Thomas Davies (who legally denies he ever made it), utilising the lack of traffic during the pandemic and a in-depth understanding of speed camera evasion. This (legally-theoretical) journey would give Davies an average speed of 87mph, a number which I'm sure would make Godwinson, Carey, and Turpin proud.

^The core motorway network of England & Wales. Note the similarity to the previous map of the Mediaeval and Roman Roads.

^The core motorway network of England & Wales. Note the similarity to the previous map of the Mediaeval and Roman Roads.

Its easy to see roads as downstream of civilisation: infrastructural requirements for transport between established nodes of commerce and culture. However as I've shown this is often the other way around. The places we live can be determined by their proximity to roads, just as much as they can be determined by their proximity to rivers or resources. The system of roads we have in this country are ancient, older than the vast majority of cities, and therefore have become as much a part of the landscape as mountains and coastlines. Despite new technologies in rail and air transport, the humble path remains the most accessible and universal form of link between anywhere. Come oil shortages, rail strikes or governmental collapse, we will still be able to follow the pigtracks from A to B. And if British civilisation were to begin afresh, I'm sure we'd see the familiar forms of Icknield, Watling, Ermine and Fosse straddle old England anew.