Welcome to Maid Spin, the personal website of iklone. I write about about otaku culture as well as history, philosophy and mythology.

My interests range from anime & programming to mediaevalism & navigation. Hopefully something on this site will interest you.

I'm a devotee of the late '90s / early '00s era of anime, as well as a steadfast lover of maids. My favourite anime is Mahoromatic. I also love the works of Tomino and old Gainax.

To contact me see my contact page.

I was out on a journey in the far reaches of the Central Line, in that strangely liminal part of England situated within the great wall of the M25, but within smelling distance of farmland and paddocks. I'd taken the underground out to visit a mysterious place I'd discovered whilst trawling through old photographs of housemaids from the archives. Now the fringe of an unassuming suburb in Essex, these few acres were once the "maid utopia" of England: a walled model village wherewithin girls were be trained in the art of domestic servitude. Within these grounds a realisation of the romantic ideal of England-past was constructed, a backlash against the era's mode of reckless and un-English "progress".

Founded in 1866 and still going strong today, "The National Incorporated Association for the Reclamation of Destitute Waif Children" was founded by Dr Thomas Barnado, who's name is still household today. Barnado spent his life dedicated to the welfare of poor children, building several large campuses across England for the resettlement and education of orphaned and abandoned children. The very epitome of the Dickensian philanthropist, Barnado was fueled by a muscular and evangelical religiosity, as well as a strain of reactionary traditionalism that often verged on neo-feudalistic.

^A aerial view of the remaining village green facing NW. The clocktower is in the bottom left, the church on the right, and the modern Barnados Charity Headquarters at the top.

^A aerial view of the remaining village green facing NW. The clocktower is in the bottom left, the church on the right, and the modern Barnados Charity Headquarters at the top.

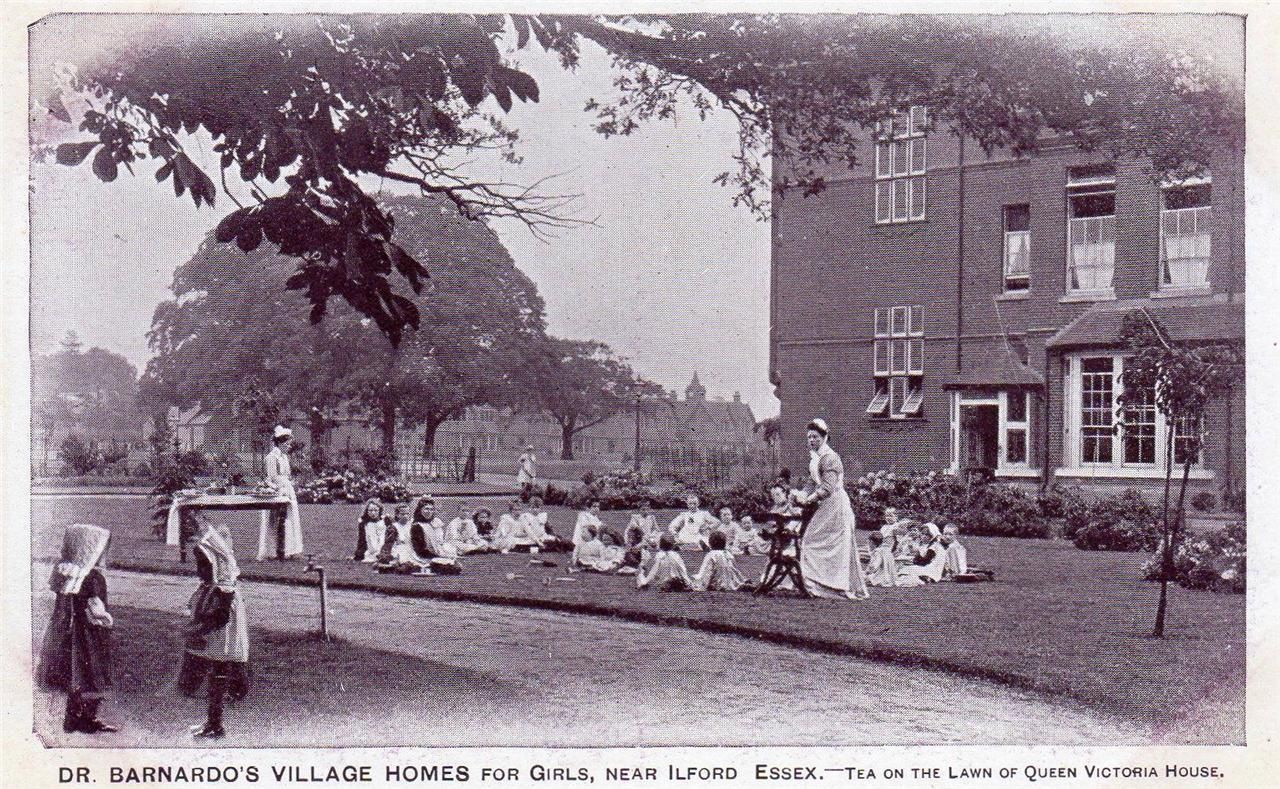

The village itself was built in 1875 on what was greenfield pastureland in the area of Barkingside, Essex. Centred on a "village green", the settlement initially consisted of two-dozen half-timber and brick cottages housing up to twenty girls each, built in a faux-vernacular style. Each cottage was under the charge of a "mother", whom were selected personally by Barnado and by prerequisite had to be unmarried, teetotal and devoutly protestant. The cottages (all named for wildflowers) acted like miniature households in and of themselves. Cooking and cleaning for themselves under the watchful guidance of their mother. Another two greens were later built south of the first, expanding the village to nearabouts 1500 children and 100 staff (almost entirely women) by 1906. At the nexus of the three greens is the "village-hall" and clock-tower, as seen in the header photo. A whimsically beautiful building for sure, but one which immediately strikes as "off". In fact the whole place feels "off": like a themepark of little England or a 1:1 scale model-village. In the corner of the village sits the non-demoninational "Children's Church", where the saved children would be taught the catechism and encouraged to live a life of piety, which included a life pledge against alcohol. The slightly strange religion of Barnados is evident in all of his works: evangelical, non-conformist and sometimes esoteric. Surrounding the village on all sides was a (now deconstructed) wall, punctuated by wrought iron gates; keeping the sins of the world out and his East-End savelings in. In effect Barnados was constructing an little English Eden: within its walls its inhabitants could live out a pure life free from the burdens of the modern outside world. He even had them play-act a mediaeval calendar of village festivals, such as maypole-dancing and singing folksongs, hoping to reconstruct the "Paradise Lost" of pre-industrial rural England. The girls kept ponies, grew vegetables and baked their own bread. Electric lighting, "modern fabrics" and even newspapers (and eventually radios, when they came along) were forbidden, in an attempt to shield the girls within from the darkness without.

^Afternoon tea at Barkingside.

^Afternoon tea at Barkingside.

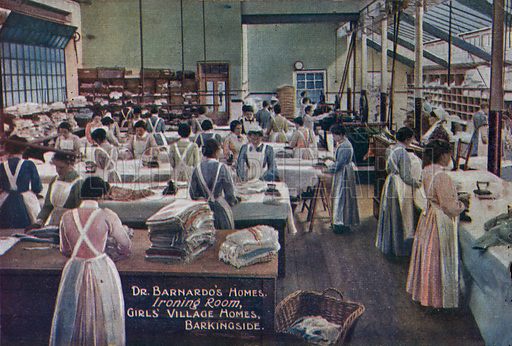

Although romantic, Barnados' vision was also pragmatic in accordance with his reformed religion. The girls were taught a strict curriculum of practical domestic studies, readying them for a life as housemaids for the great and good. He saw such a profession as the best way to live morally in accordance with natural order. The English class system, although forever morphing, even today retains its role as the core structural trunk of British society, and the way Barnados saw it, to live in harmony with the system is to live happy and free. Over the course of several years, girls were taught vital skills like ironing, embroidery, laundry and etiquette; but they were also given a basic higher education: music, poetry, literature. Missing of course were the "scientific studies" Barnados had no time for, which were emblematic of the downfall of British society he was trying to reverse. After their tenure at Barkingside, the girls would be helped into employment through an agency provided by Barnados. They were placed into stately homes and estates across the country to work in a position that aligned to whatever field of maid-studies they most naturally aligned to. Even these places of work would be vetted by Barnados; only those employers deemed upstanding would be considered, and girls were encouraged to resign and return to Barkingside if they found their employ unvirtuous. The philosophy was that if the girls could be slotted back into the position in society they should rightly have taken, they could reap the benefits of all that "England" had to offer.

^Girls practising ironing at Barkingside.

^Girls practising ironing at Barkingside.

What Barnados was taking for granted was something that has been lost in modern England, and which was fading even in his time. That is the manorial village as the fundamental unit of British society. One family, lord by right of birth and history, with a supporting retinue of obedient servants who would want for nothing. This mutually beneficial contract was the "noblesse oblige" of the manor lord: his pastoral responsibility for the lives of his villagers, both wordly and spiritual. In return for their life service, he would repay them with safety, security and satisfaction. By placing these children into the homes of the wealthy, Barnados was not looking for the "upward social mobility" or "trickle-down economics" of today's social engineer, but rather that they would live an honest life of obedient servitude. For him "freedom" was not a right to chaos, but the chance to live in accordance with order.

Barkingside Village persisted for an almost unbelievably long time. The last girls through its gates left in 1991, a 116-year old experiment. The homes were sold off as private dwellings, with the two later greens being built over with new residential buildings. Barnados Charity is still headquartered there, albeit in a new construction to the North. The quaint little green now looks worse for wear. The fountains are broken and weathered, and the cottages are looking tired. Such a place is not compatible with modern sensibilities.

^Some remaining cottages on Barkingside Village Green when I visited.

^Some remaining cottages on Barkingside Village Green when I visited.

But Barnados' philosophy is not dead. Ever since the seismic shift of the Industrial Revolution a subdued yet strong desire for a return to the "old system" has pervaded British society. In the Victorian Era this was manifest in the constructed societies of the idealists: Barkingside is one, but Bourneville (home of Cadbury's Chocolate) is another, and many a workhouse sat upon the same principles. Later came the "garden city movement", seeking to construct new-towns free from the chaos wrought by factories and industry. Letchworth and Welwyn sit miles few north of Barkingside, two of the earliest examples. The movement has evolved but remained at the heart of British city-planning, but even so it has almost always failed in its goals: Milton Keynes, Redditch, postwar Coventry, even the King's own Poundbury. These "new olds" fail to create places that are believable: only those who have boiled the ideal down to a science could ever believe in such places. It seems this notion of "Little England" has an ineffable quality: all those who attempt to manifest it are doomed to destroy it. In a way the true nature of this vision has been lost, nobody remembers the way things truly used to be. Modern advocates are guided by the facsimiles crafted by artists: Rupert the Bear, Lord of the Rings, Narnia, The Kinks Village Green, Trumpton, Hot Fuzz. One could align it with the growing mass of the English "new right", but its clear to the true believer that not UKIP nor Reform could ever embody a movement so violently modest. And so this certain strain of English yearning buckles under its own uncertainty and inability to act, busying itself with real ale, heritage railways and, yes, model villages.

"I miss the village green, and all the simple people."